Audubon Park Legacy

of Charles Lewis Johnson

in the City of New Orleans

Audubon Park – An Urban Eden, by L. Ronald Forman, Joseph Logsdon with John Wilds (1985)

Excerpts:

When John Olmsted went to work after most of the structures of the 1884-1885 Cotton Exposition had been dismantled, he found the site almost ideal for development as a park. Remaining from Pierre Foucher’s eighteenth-century plantation was a stand of imposing oak trees that the designer said gave Audubon ‘a natural advantage over the majority of American parks.’ The mild climate and the alluvial soil, resulting from centuries of flooding by the great river, almost guaranteed the thriving of plants and trees. Olmsted planned the park to be ‘typical of the State of Louisiana, its climate, soil, tree and flower growth.’ Succeeding generations of park commissioners have responded to the dictum of commissioners John Ward Gurley, Jr., and Lewis Johnson in 1895 that ‘our successors will hold us responsible for the work we do.’ Today’s acorn is the prized oak of the late twenty-first century.

The classical St. Charles Avenue entrance was designed by John Olmsted himself. Mrs. Maurice Stern provided the money for the complex, of a design reminiscent of French and Italian Renaissance architecture, in memory of her husband. Through this gate have streamed many thousands of park-goers, including students at Tulane University and Loyola University of the South, which have campuses directly across St. Charles. The park has been a rendezvous for students…….Even before the exposition grounds were dismantled, the city council created a new commission on May 31 to maintain the park as well as the neutral grounds of St. Charles Avenue. The councilmen insisted that the twenty-four member commission could not use any city funds to maintain or improve the park, but the mayor, Joseph Guillote, appointed to the board some influential leaders who took a serious interest in their new charge. To demonstrate his own concern, the mayor called the first meeting to order on June 5 and witnessed the election of John Ward Gurley, Jr., as the commission’s first president, a position he held until 1903. Together with Lewis Johnson, another prominent businessman, Gurley provided the leadership that willed a true park into existence. More than any others, these two men deserve designation as the fathers of Audubon Park…

.....In 1890 Lewis Johnson got the commission to form an auxiliary body, the Audubon Park Improvement Association, to collect private funds ‘free from all political or otherwise objectionable influence.’ Within a month, the new group recruited over three hundred members and collected $1500 in annual dues. Optimism increased……..Together with a newly revived City Park commission, the Audubon board pestered the city council again for funds, and in late 1892 their joint efforts finally paid off. The council gave them a special appropriation of $5000 to be shared equally by the two parks. [City Park and Audubon Park] By the summer of 1893, a bold new idea took hold of the leaders of the commission, particularly J. Ward Gurley and Lewis Johnson. It was time to fashion a full-scale plan for the park’s future development. Gurley approached several of the nation’s leading park designers and invited them to submit their ideas for a park plan based on a million-dollar expenditure. One of the letters was sent to the most famous of all designers of American parks, Frederick Law Olmsted, who had begun his career as superintendent and designer of Central Park in New York City…….Gurley and Lewis Johnson had made a decision that they eventually brought before the public in an ambitious ‘Address to the People’ in 1895……But the commission had no money to match its ambitions…

.….(In 1896) the legislature gave them no money but mandated that the city of New Orleans provide an annual appropriation of $15000 to each of the parks. With this annual income, Gurley and Johnson now pressed for a master plan by professional landscape architects. After a heated debate, Johnson succeeded in convincing his fellow commissioners that it was criminal folly to start any new project without a comprehensive plan. The board set aside 25% of the 1897 appropriation for a professional design. The timing was perfect. Just as the Audubon commissioners took these important steps, they were invited to attend the first park convention in US history, which met in Louisville in the late spring of 1897.

Lewis Johnson led the New Orleans delegation and read a paper on the painful history of parks in New Orleans. There he met landscape architects John C. Olmsted and Warren H. Manning, whom he convinced to compete for the contract to design Audubon Park. Gurley and Johnson were jubilant over their good luck. They did not know it at the time, but their real luck lay in the fact John C. Olmsted, for his own reasons, wanted very much to win this particular contract. Although the board, the neighbourhood, and the press applauded his initial work, further implementation of Olmsted’s plan stopped for more than a decade.

Lack of money caused most of the delay, but a change in board leadership also played a role. In 1903 a disgruntled former defendant murdered J. Ward Gurley, who was the city’s district attorney. The death of the park’s first president, the powerful, single-minded leader who had backed Olmsted from the beginning, was a blow, for Gurley had refused steadfastly to tolerate any fundamental alteration in Olmsted’s plan for Audubon Park. Lewis Johnson, who took over the board presidency, was another stalwart defender of Olmsted, but he felt more obliged to placate those on the board and in the community who wanted more money spent on immediate recreational facilities for the park. The struggle was not easy.

For a year the park commission suspended their contract with Olmsted because of a shortage of funds and new questions about his overall design. Johnson apologized to the designer, explaining that many of the board’s old members had died and had been replaced by ‘new material that has to be wrestled with to bring them into line.’ And there was a lot of wrestling. The commissioners quickly turned down a beer hall, a vaudeville house, a dairy farm, and a pecan tree plantation, and just as easily accepted a restaurant (the famous tearoom), a new carousel, a private aquarama show, and a polo club. But they argued fiercely over a streetcar loop through the park, a large stadium, an art museum, and a statue of Jefferson Davis for the St. Charles entrance.

…….When Olmsted came to the city in the midst of this battle in late 1909, some of the board demanded substantial alteration and others complete abandonment of his original design for the park. Johnson, too ill to attend these meetings while Olmsted was in the city, could not mount his well-practiced defense of the planner. But within a few weeks he rose from his sick bed and mustered the energy for one last burst of will. He pulled out Olmsted’s plans, put them on public exhibit, and badgered the board into voting renewed support for them – for making Audubon ‘essentially a landscape park.’

Moreover, the board asked Olmsted to render them a report detailing a step-by-step plan for future implementation of his design. Within a few months Johnson died. His determination, like that of Gurley’s, had kept alive the dream of an Olmsted park in New Orleans. He did not live long enough to read Olmsted’s 1910 report, but a new board member came forward to take up the mantle of leadership.

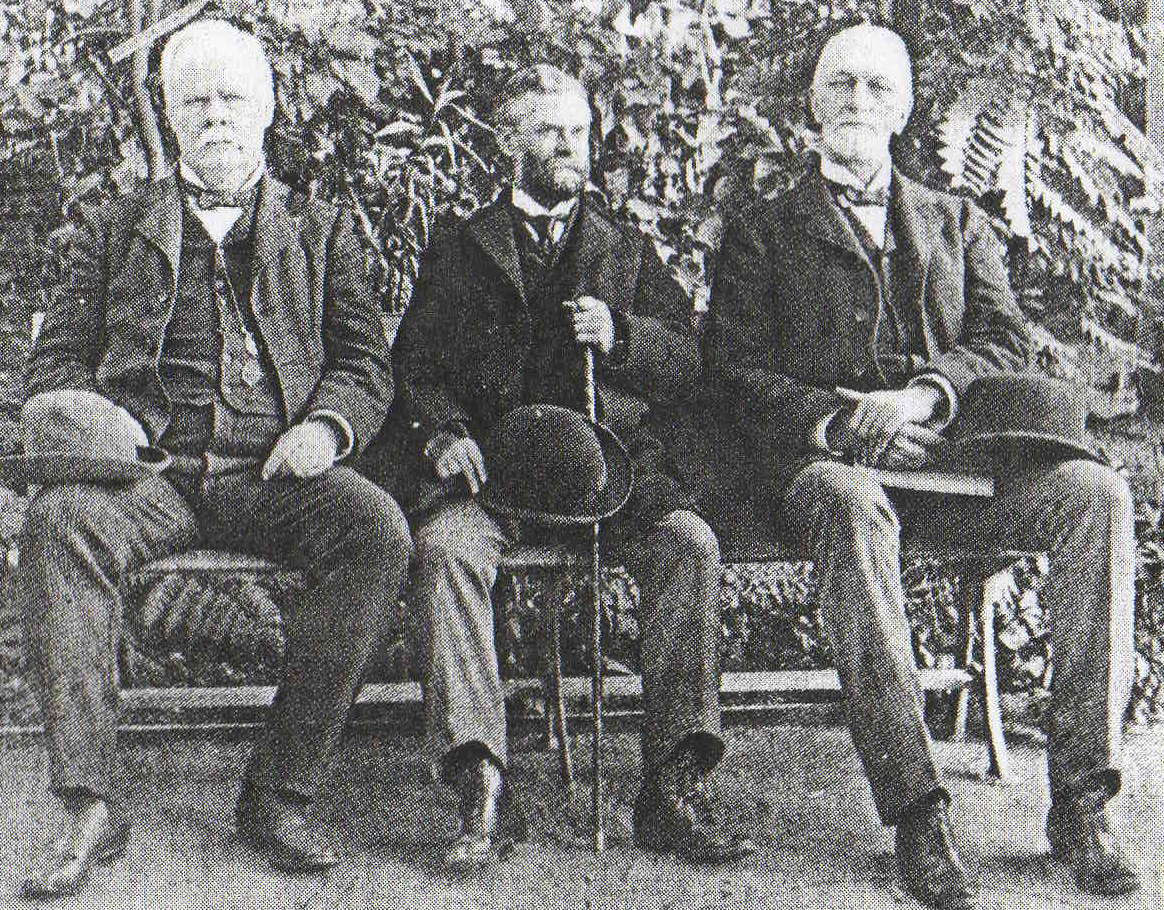

"John Ward Gurley is in the center, and Lewis Johnson is on the right. The person on the left has not been identified. Both Gurley and Johnson were natives of New Orleans and influential in city politics and business. Gurley, a lawyer, served as District Attorney for Orleans Parish, and Johnson, the president of Johnson Iron Works, acted as the head of the Sewerage and Water Board. Gurley was the first president of the Audubon Park Commission (1886-1903) and Johnson was the second (1903-1910)."

Back to Charles Lewis Johnson Family Page

Back to Wendy’s Ancestral Tree

Last updated: 20 July 2020.